The short version is that co-resolution is not the unauthorized practice of law and co-resolvers are not acting as attorneys. The long version is as follows:

I.

The Right to Choose an Alternative

to Litigation and Legal Assistance

First,

it must be noted that parties have the right to mutually choose the process

(e.g., facilitated negotiation, arbitration, litigation) by which they handle

their dispute. This means that parties

have the right to not litigate their dispute and not approach attorneys.[1] Judicial wisdom supports the right to avoid

litigation,[2]

and the Federal Arbitration Act (which is enacted verbatim in the Ohio

Arbitration Act[3]) has

allowed parties to enforce agreements to approach non-legal/non-court processes

of dispute resolution.[4] Taking a look beyond the quasi-judicial

process of arbitration, the lack of definition of “arbitration” in the Federal

Arbitration Act[5]

has led courts to grant parties broad discretion in the procedures by which

they handle their disputes without approaching courts or attorneys.[6] To be clear, I am not arguing about the enforceability of an agreement to stay litigation and compel

co-resolution—I am merely, pointing out that the law affords parties the

ability to choose non-court/non-legal forums in handling their disputes. However, going beyond the right to not

litigate, the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct impose a duty on

attorneys to inform clients of feasible alternatives to litigating their legal

rights,[7]

and “[s]everal jurisdictions encourage, but do not require,

lawyers to inform clients of ADR options.”[8] Thus, if both parties agree to forgo

litigation and legal assistance, they may temporarily “contain” their dispute

in an alternative process to litigation.

The

key result of this right to not litigate is that parties to a dispute have the

right to choose between bringing either attorneys or non-attorney advocates to

the negotiation table in these contained or mutually-agreed-to processes. Tried

and true examples of non-attorney advocates chosen over attorneys in resolving disputes

include union representatives,[9]

financial experts hired as representatives in securities disputes,[10]

sports agents,[11] and

lay advocates in administrative hearings concerning welfare benefits,[12]

Social Security applications,[13]

and others.[14] Even in active court cases, parties can avoid

legal expenses by agreeing to employ CASA advocates, instead of attorney Guardians ad

Litem, to act as advocates in the litigation process.[15]

Access

to non-legal advocates does not equate to a diminution of justice in the

system. Parties who have access to lay

advocates have, in some studies, expressed greater satisfaction with their

non-attorney advocates than similarly-situated parties did of their attorney

advocates.[16] Non-attorney advocates can use expertise in

areas other than legal knowledge during a negotiation[17]

and can be more accessible to parties who cannot afford the assistance of a

legally trained and licensed attorney.[18]

Co-resolution

applies this concept by offering communication, coaching, and cooperative negotiation

skills as the substantive area of expertise of the non-attorney advocates.

II.

Conflict Coaching and Ethical

Concerns with Non-Attorney Negotiators

Co-resolution

provides each disputant with a cooperative “conflict coach” to directly assist

them in the negotiation.[19] Conflict coaching is “a one-on-one process in

which a trained coach helps individuals gain increased competence and

confidence to manage and engage in their interpersonal conflicts and disputes.”[20]

This process emerged in the 1990s from

the fields of alternative dispute resolution and executive coaching[21]

and tends to promote the cooperative approach to resolving disputes that is

described in such books as Getting to Yes.[22] Some have argued, because both law-focused

attorneys and communication-focused non-attorneys each offer unique benefits in

a cooperative, non-legal negotiation forum such as mediation,[23]

that ethical rules concerning the unauthorized practice of law should be

modified to allow for the direct assistance of either attorneys or

non-attorneys.[24]

However,

because conflict coaches hold themselves out as negotiation assistants, if they

operated independently and sat at the table during a negotiation it might

create ethical concerns with the unauthorized practice of law.[25] While this concern has not been explored in

the literature or the case law, problems may arise when the non-attorney

conflict coach directly assists a party in negotiating a pending legal action

against an attorney.

Consider

a situation in which one party to a pending legal action hires a non-attorney

conflict coach to provide one-on-one assistance in negotiating cooperatively

and the other party hires an attorney. The

disputant with the cooperative, non-attorney conflict coach may be at a

disadvantage in the negotiation because the party with the attorney would be

able to use competitive negotiation tactics to take advantage of cooperative

negotiation behavior and would be able to offer a one-sided perspective on how

the court would handle the case if resolution was not reached. This concern appears to be pinpointed by Ohio

case law on the subject.

The

Ohio Supreme Court has defined the practice of law as “(1) legal advice and

instructions to clients advising them of their rights and obligations; (2)

preparation of documents for clients, which requires legal knowledge not

possessed by an ordinary layman; and (3) appearing for clients in public

tribunals and assisting in the interpretation and enforcement of law, where

such tribunals have the power and authority to determine rights of life,

liberty, and property according to law.”[26] While the Court initially held that the

practice of law is not limited to appearance at court,[27]

when a district court applied this ruling to define the practice of law as “all

advice to clients and all action taken for them in matters connected with the

law,” the Ohio Supreme Court overruled this as being an overbroad definition of

the practice of law.[28]

In

dealing with non-attorneys engaging in the unauthorized practice of law by

assisting or participating in negotiations, the Ohio Supreme Court has found

such violations when a person, on behalf of another and without the consent of

both parties, contacted the opposing party with a letter that implied a

discrimination claim, threatened legal action, and offered a $200,000.00

settlement.[29] Obviously, evaluation of legal rights and the

dollar value of a potential court case are actions that should only be

conducted by attorneys. The Ohio Supreme

Court has cited this case, stating “[w]e have repeatedly held that nonlawyers

engage in the unauthorized practice of law by attempting to represent the legal

interests of others and advise them of their legal rights during settlement

negotiations,”[30]

in addressing situations in which non-attorneys negotiate directly against

attorneys[31]

or negotiate pending litigation against the other party directly.[32]

The

common thread in these cases (and the key distinction between these cases and

the fully-legal and common non-attorney advocates described in the previous

section[33])

is that the non-attorneys who were found in violation of UPL statutes were

acting alone and outside of a defined process that is “contained” from

court-involvement, such as mediation, arbitration, or administrative hearings. Outside of defined processes such as

mediation and arbitration, “which clearly represent a track

apart from the traditional litigation route, negotiation remains for many

nothing more than a component of the litigation process.”[34] Out in the open, litigation is a possibility looming

over negotiations and, therefore, non-attorneys may end up negotiating against

attorneys.

The

purpose of unauthorized practice of law statutes is to protect the public from

unskilled legal advice, not to limit the type of advocacy that parties can mutually

choose.[35] So long as both parties agree to the process,

the situation becomes akin to mediation and arbitration and less akin to one

person operating an “advocacy” service.

Thus,

a conflict coach who is operating independently of a defined system may face

unauthorized practice of law issues. But

this does not mean that the direct assistance in cooperative communication and

negotiation skills, offered by conflict coaches, is a benefit that is beyond

the reach of opposing parties who both want it.

III.

Co-resolution as an Ethical

Process for Non-Attorney Negotiation Assistance

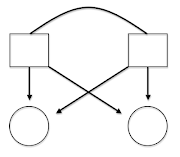

Co-resolution

addresses these potential ethical issues by providing each party to the dispute

with a conflict coach and defining the process as a contained, separate dispute

resolution process.

First

introduced in 2008, co-resolution is a facilitated negotiation process in which

two dispute resolution professionals operate as a single service and act as a

team of coaches, each assisting one disputant in negotiating under their

interests.[36] Parties approach this process together,

participate voluntarily, and, afterwards, are free to pursue legal or other

non-legal processes if desired. Both

coaches (“co-resolvers”) make it explicitly clear that they are not acting as

attorneys and are only assisting in cooperative negotiation and communication

techniques as they facilitate a resolution to the dispute. Co-resolvers do not offer legal advice and

direct the parties to consult with attorneys if they ask questions regarding

their legal rights.

Thus,

all of the rules that apply to mediation as a process for facilitated

negotiation also apply to co-resolution.

For example:

1.

The

parties must both agree to engage the process—neither side is able to compel

the other into participating against their will;

2.

Participation

is voluntarily and either party is free to discontinue the process (disengaging

both coaches) at any time;

3.

The

coaches only facilitate communication, and the parties maintain

self-determination over the outcome;

4.

The

coaches do not offer or provide legal advice;

5.

The

coaches (like mediators) can be attorneys or non-attorneys, however, within the

process they are not acting as attorneys;

6.

Each

party can bring an attorney to provide legal advice during the process;

7.

The

process ends when the parties reach an agreement or an impasse.

However,

unlike mediation, the co-resolvers are not neutral—each one assists one party

in negotiating a resolution of the dispute.

The

unique benefit that co-resolution offers over other forms of

negotiation-advocacy is that, because the co-resolvers act as an ongoing team

within a contained process, each co-resolver is able to know that the opposing co-resolver

will only support cooperative negotiation strategies. This dynamic is the result of

cooperation-inducing forces described in game theory and studies of

negotiation.

First,

game theory (“the study of mathematical models of conflict and cooperation

between intelligent rational decision-makers”[37])

has shown that rational decision-makers will compete (seek an individual advantage)

rather than cooperate (seek mutual benefit) in a single interaction.[38] This dynamic occurs because each knows that

competition garners marginal gains over attempting to cooperate. Furthermore, each knows that the other side

is operating under similar incentives to compete and must therefore compete to

protect themselves from the other side’s competitive moves. For example, consider attorneys who can

either act as tough competitors or conciliatory cooperators: because each

attorney operates independently (is chosen by one party), each attorney is

under incentive to present themselves as a tough competitor and each party is

under incentive to hire a tough attorney (for fear of what kind of attorney the

other side will hire).[39]

On

the other hand, if the decision-makers were to interact on an indefinitely

repeating basis, both would seek to cooperate.[40] The reason for this is that repeated

cooperation (where both receive a mutually-acceptable outcome) will, over time,

garner a greater outcome for each individual than repeated competition (where both

parties attempt to undermine each other and end up with either a limited

outcome or no outcome at all). The power

of future interaction is visible in the legal field. As attorneys (independent advocates hired

separately on a case-by-case basis) became more numerous over the past

half-century, causing them to interact less frequently, their competitiveness

has increased and their civility has decreased to the point of “crisis.”[41] However, in situations where attorneys

interact frequently—such as small towns,[42]

small pools of public defenders and prosecutors,[43]

and practice groups of collaborative lawyers[44]—cooperation

and civility are enforced and protected through the advocates’ ongoing working

relationship with each other. As a

result, the ongoing interaction between the co-resolvers should, in theory,

keep their negotiation behavior and coaching efforts cooperative.

Next,

studies of negotiation and dispute resolution have confirmed the real-world

power of these strategic theories. In

informal negotiation, where there are no rules or oversight that can curb

competition, the above-described game-theory pressures towards competition in a

single negotiation are especially prominent.[45] Studies have shown that, as independent

advocates, attorneys are especially prone to engage in deception in settlement

negotiation.[46] However, repeated interactions between the

same players have been shown to produce cooperation by “cast[ing] a shadow back

upon the present and thereby affect[ing] the current strategic situation.”[47] Supported by psychological studies of

negotiation behavior, this is the reason that “[s]avvy

negotiators expend time and effort to build a positive personal relationship

with their opponents because such relationships can pay dividends.”[48] The ongoing relationship and the negotiation rapport

between the co-resolvers should therefore contribute to smooth interactions and

amicable coaching efforts.

Thus, because co-resolvers operate

through an ongoing working relationship, the assistance they provide to

opposing parties is cooperative in nature—the repeated interaction between the

co-resolvers motivates cooperative behavior, and each party can know that the

opposing co-resolver will only assist the opposing party in cooperative

negotiation behavior. This dynamic of

reliable cooperation has been demonstrated through participant surveys and

anecdotal observations gathered in co-resolution pilot projects in the United

States and Canada, strongly indicating that parties felt loyally supported in a

cooperative negotiation environment.[49]

However, more important to the point

of this letter, the insulating effect of the co-resolution process allows the

co-resolvers to serve as conflict coaches without drawing concerns relating to

the unauthorized practice of law. Once

again, like mediation, co-resolution is a defined, voluntary process. The parties approach it together (each

desiring to have the benefit of a negotiation coach and to work across from a

cooperative opposing coach), participate voluntarily, and either reach

agreement or impasse. The co-resolvers

individually assist their respective parties in communicating and negotiating

effectively while also acting as a team in guiding both parties toward a mutual

resolution. Because the co-resolvers

operate within a defined process, in which both parties agree to participate,

there is no danger that a co-resolver will act as an attorney, operating independently

and conducting settlement negotiations against an actual attorney under pending

litigation.[50]

Furthermore, parties to

co-resolution, like participants in mediation, operate apart from the exercise

of their legal rights[51]

but do not fully give up these rights.[52] Within the facilitated negotiation of mediation

or co-resolution, the parties are able to exercise self-determination and

define their own agreement rather than choosing from options that would be

imposed by a court.[53] However, these parties are also free to walk

away from the process, take agreements to independent attorneys for approval,

and proceed to litigation if they so desire—therefore, they never give up legal

rights or legal assistance by participating in co-resolution. But, instead of relying on the parties to

understand and exercise their access to attorneys and the courts, co-resolvers

explain that the process is voluntary and that either party can terminate the

process at any time.[54] Regardless, parties who reach out-of-court

agreement—either through co-resolution, mediation, or settlement negotiations

facilitated by independent attorneys—forgo their legal rights to some degree

but apparently value this decision over the uncertainty of a judicial

determination of their case.[55]

Furthermore, the courts have recognized

a strong public policy that favors settling cases efficiently to avoid prohibitive

legal fees for the parties.[56]

Skeptics of co-resolution may see

two coaches sitting next to separate parties, assisting them in discussing and

negotiating their dispute, and improperly label the process as the unauthorized

practice of law or a violation of legal ethics.

However, doing so would ignore the plethora of non-attorneys who assist,

negotiation, and advocate for parties, affecting potential legal rights in many

fields and, yet, operating outside of potential court involvement.[57]

The key to keeping non-attorney

advocates ethical is containing or proscribing their assistance away from

pending litigation—so long as the non-attorney advocates are operating in a

defined process, they are not in danger of taking the role of legal

advocate. Co-resolution is a defined

process, mutually undertaken by both parties like mediation and arbitration, and

also like mediation and arbitration, it is clearly separate and apart from the

litigation process.[58]

In conclusion, the conflict coaches

who assist the parties in communication and negotiation within the

co-resolution process are not acting as attorneys and should not be in

violation of legal ethics rules or unauthorized practice of law statutes.

[1] Blinco v. Green Tree Serv.,

Inc., 366 F.3d 1249, 1252 (11th Cir. 2004) (citing , Mitchell v. Forsyth,

472 U.S. 511, 526 (1985) (“The arbitrability of a dispute similarly gives the

party moving to enforce an arbitration provision a right not to litigate the

dispute in a court and bear the associated burdens”).

[2] See Hon. Ron Spears, Lincoln Warnings: ‘You Have the Right to

Avoid Litigation…’, 94 Ill. B.J.

438 (2006).

[3] Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §§ 2711.01-.24 (West

2008). The Ohio Arbitration Act applies to written contracts and expressly

declares them “valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, except upon grounds that

exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.” § 2711(A). This

language is exactly the same as the language in the FAA. See 9 U.S.C.A.

§ 2 (West 2008).

[4] United

Steelworkers of Am. v. Warrior & Gulf Navigation Co., 363 U.S. 574

(1960) (ruling that a federal court may compel an employer to submit a union's

grievance to arbitration); United Steelworkers of Am. v. Am. Mfg. Co.,

363 U.S. 564 (1960); United Steelworkers of Am. v. Enter. Wheel & Car

Corp., 363 U.S. 593 (1960). Like the

Federal Arbitration Act, the Ohio Arbitration Act has similarly been interpreted

to create a presumption of validity regarding the enforceability of written

contracts containing arbitration agreements. OHCONSL § 21:3. For Ohio case law, see Maestle v. Best Buy

Co., (2003) 100 Ohio St.3d 330, 334 800 N.E.2d 7 (“We hold that a trial

court considering whether to grant a motion to stay proceedings pending

arbitration filed under R.C. 2711.02 need not hold a hearing pursuant to R.C.

2711.03 when the motion is not based on R.C. 2711.03.”), and describing the

strong public policy favoring arbitration/mediation alternatives to the courts,

see Williams v. Aetna Fin. Co., 83 Ohio St.3d 464, 471, 700 N.E.2d 859

(1998), ABM Farms, Inc. v. Woods, 81 Ohio St.3d 498, 500, 692 N.E.2d 574

(1998). Where there are doubts regarding the application of an arbitration

clause, such doubts should be construed in favor of arbitrability. Council

of Smaller Enterprises v. Gates, McDonald & Co., 80 Ohio St.3d 661,

666, 687 N.E.2d 1352 (1998)

[5] Thomas J. Stipanowich, The

Arbitration Penumbra: Arbitration Law and the Rapidly Changing Landscape of

Dispute Resolution, 8 Nev. L.J. 427, 434-435 (noting “the silence of the

FAA and UAA regarding the definition of arbitration, coupled with the fact that

federal and state statutes establish no formal requirement that arbitration

agreements be explicitly identified as such…”).

[6] Salt Lake

Tribune Publ'g Co. v. Mgmt. Planning, Inc., 390 F.3d 684, 690 (10th Cir.

2004) (“Parties need not establish quasi-judicial proceedings resolving their

disputes to gain the protections of the FAA, but may choose from a broad range

of procedures and tailor arbitration to suit their peculiar circumstances.”).

[7] Model

Rules of Prof’l Conduct R. 2.1 cmt. (1983) (stating that “when a matter

is likely to involve litigation, it may be necessary under Rule 1.4 to inform

the client of forms of dispute resolution that might constitute reasonable

alternatives to litigation”).

[8] Robert F.

Cochran Jr., Professional Rules and Adr: Control of Alternative Dispute

Resolution Under the ABA Ethics 2000 Commission Proposal and Other Professional

Responsibility Standards, 28 Fordham

Urb. L.J. 895, 904 (2001)

[9] Lisa B. Bingham

et al., Exploring the Role of Representation in Employment Mediation at the

USPS, 17 Ohio St. J. on Disp. Resol.

341, 359, 363-66 (2001) (presenting surveys of mediation participants who were

unrepresented, represented by an attorney, represented by a fellow employee, or

represented by a union representative).

[10] Justine P. Klein, Non-Attorney

Representation, 63 Fordham L. Rev.

1605, 1608 (stating “They also took the position that non-attorney

representatives took these cases at a cost that was less than that which would

be charged by lawyers. They also made the argument that because a number of

non-attorney representatives were former securities industry people, they

provided a level of expertise that a customer doesn't always get when retaining

a lawyer . . . It is clear that these

non-attorney representatives do provide some access and they do provide a freedom

of choice.”).

[11] Stacey B.

Evans, Sports Agents: Ethical Representatives or Overly Aggressive

Adversaries?, 17 Vill. Sports & Ent. L.J. 91 (2010) (“Degree Directory

defines a sports agent as someone who “handles contract negotiations, public

relations issues and finances, and he or she will often procure additional

sources of income for the athlete (such as endorsements).”).

[12] See Earl

Johnson, Jr., Justice for America's Poor in the Year 2020: Some

Possibilities Based on Experiences Here and Abroad, 58 DePaul L. Rev. 393, 416-417 (2009).

[13] Drew A.

Swank, Non-Attorney Social Security Disability Representatives and the

Unauthorized Practice of Law, 36 S. Ill.

U. L.J. 223, 224 (2012) (“Before

the Social Security Administration, Bob's actions are not only completely

legal, they are a common, everyday occurrence for approximately five thousand non-attorney representatives.”).

[14] Id. at 234 (“As administrative agencies were designed without the

formalities and rules of the courts, they were ideally suited for non-attorney representatives. As the number of administrative

agencies increased, so too did the opportunities for non-attorneys to practice

law. Historically, non-attorneys have routinely appeared before certain federal

administrative agencies.”).

[15] Gerard F.

Glynn, The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act-Promoting the Unauthorized

Practice of Law, 9 J. L. & Fam.

Stud. 53, 74 (2007) (“The non-lawyer advocate can provide the

investigation, monitoring and follow-up that lawyers do not have the time or

receive adequate pay to do…”).

[17] Herbert M.

Kritzer, Legal Advocacy: Lawyers and Nonlawyers at Work 77, 111-49

(1998) (noting that “formal training (in the law) is less crucial than is

day-to-day experience in the unemployment compensation setting”); see also Russell Engler, Connecting

Self-Representation to Civil Gideon: What Existing Data Reveal About When

Counsel is Most Needed, 37 Fordham

Urb. L.J. 37, 38 (2010), at 3, 47-48 (noting importance

of not just any advocate, but an advocate with specialized expertise).

[18] Kay Hennessy Seven and Perry A.

Zirkel, In the Matter of Arons: Construction

of the Idea's Lay Advocate Provision Too Narrow?,

9 Geo. J. on Poverty L. & Pol'y

193 (2002) (“Non-attorneys or lay advocates with specialized knowledge can facilitate

access to the legal system for parties with restricted financial means who do

not have the legal skill or knowledge to represent themselves.”); see

generally Marcus J. Lock, Increasing

Access to Justice: Expanding the Role of Nonlawyers in the Delivery of Legal

Service to Low-Income Coloradans, 72 U. Colo. L. Rev. 459 (2001); Alex J. Hurder, Nonlawyer Legal Assistance and Access to

Justice, 67 Fordham L. Rev.

2241 (1999)

[19] See Nathan Witkin, Co-resolution: A Cooperative Structure for

Dispute Resolution, 26 Conflict

Resol. Q., 239 (2008).

[20] Cinnie Noble, Conflict

Management Coaching: The CINERGY Model 12 (2012); see also Tricia S. Jones and Ross Brinkert, Introducing the

One-on-One Dispute Resolution Process Conflict Coaching: Conflict Management

Strategies and Skills for the Individual (2008) (defining conflict coaching

as “a process in which a coach and client communicate one-on-one for the

purpose of developing the client's conflict-related understanding, interaction strategies

and interaction skills.”); see also Ross

Brinkert, ADR Plus One: Developing ADR Practice Through Coaching (May

2003), abridged version available at www. mediate. com; see also Cinnie Noble, Conflict

Coaching: A Preventative Form of Dispute

Resolution” (2002) and “Mindfulness in Conflict

Coaching (2006), both available at

www.mediate.com.

[21] Cindy Fazzi, Introducing . .

., 64 Disp. Resol. J. 90, 90.

[22] Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting

to Yes (2nd ed. 1991).

[23] Sida Liu, Beyond Global

Convergence: Conflicts of Legitimacy in a Chinese Lower Court, 31 Law & Soc. Inquiry 75, 95 (2006)

(observing that “skills required in mediation are no longer legal knowledge,

but mostly interpersonal skills and familiarity with the customs of the local

community” or “nonlegal skills”).

[24] Jean R. Sternlight,

Lawyerless Dispute Resolution: Rethinking A Paradigm, 37 Fordham Urb. L.J. 381, 411-12 (2010)

(arguing that “the need for providing emotional support, self-agency, and an

endorsement or reputational boost of the sort discussed by Sandefur may be just

as great or even greater in mediation or arbitration than in litigation . . .

[but that] . . . rather than assume that the substitution of

non-attorney-representatives for attorneys makes more sense in ADR than in

litigation, we should rethink the rules on unauthorized practice of law with

respect to all forms of dispute resolution.”).

[25] Ohio

Rev. Code Ann. §§4705.07(A): No person who is not licensed to practice

law in this state shall do any of the following: (1) Hold that person out in

any manner as an attorney at law; (2) Represent that person orally or in

writing, directly or indirectly, as being authorized to practice law; (3)

Commit any act that is prohibited by the supreme court as being the

unauthorized practice of law.

[26] Worthington City School Dist. Bd. of Edn. v. Franklin Cty. Bd. of

Revision, 85 Ohio St.3d 156, 707 N.E.2d 499, 503-504 (1999),

citing Mahoning Cty. Bar Assn. v.

The Senior Serv. Group, Inc. (Bd.Commrs.Unauth.Prac. 1994), 66 Ohio

Misc.2d 48, 52, 642 N.E.2d 102, 104.

[27] Land Title Abstract &

Trust Co. v. Dworken, 129 Ohio St. 23 (1934) (“The practice of law is not

limited to the conduct of cases in court. It embraces the preparation of

pleadings and other papers incident to actions and proceedings on behalf of

clients before judges and courts…”).

[28] Dayton Bar Association v.

Lender’s Services Inc., 40 Ohio St. 3d 96 (1988) (“the mere use of legal

terms of art…does not, standing alone…constitute the practice of law”).

[29] Cleveland Bar Assn. v. Henley, 95 Ohio St.3d 91 (2002).

[30] Cincinnati Bar Assn. v. Foreclosure Solutions,

L.L.C., 123 Ohio St.3d 107

(2009).

[31] Disciplinary Counsel v. Brown, 121 Ohio St.3d 423 (2009) (stating that “one

who purports to negotiate legal claims on behalf of another and advises

persons of their legal rights…engages in the practice of law”) (emphasis

added).

[32] Cincinnati Bar Assn., 123 Ohio St.3d 107.

[33] See Section I., supra,

footnotes 9-15

[34] Robert C.

Bordone, Fitting the Ethics to the Forum: A Proposal for Process-Enabling

Ethical Codes, 21 Ohio St. J. on

Disp. Resol. 1, 13-14 (2005) (“Unlike arbitration and mediation, which

clearly represent a track apart from the traditional litigation route,

negotiation remains for many nothing more than a component of the litigation

process.”).

[35] See In re

Opinion No. 26 of the Comm. on the Unauthorized Practice of Law, 654 A.2d

1344, 1350 (N.J. 1995); see also Morley v. J. Pagel Realty &

Ins. Co., 550 P.2d 1104, 1107 (Ariz. Ct. App. 1976) (“purpose is to protect

the public from the intolerable evils which are brought upon people by those

who assume to practice law without having the proper qualifications”) (quoting Gardner

v. Conway, 48 N.W.2d 788, 794 (Minn. 1951)); Beach Abstract & Guar.

Co. v. Bar Ass'n, 326 S.W.2d 900, 903 (Ark. 1959) (“This prohibition by us

against others than members of the Bar of the State of Arkansas from engaging

in the practice of law is not for the protection of the lawyer against lay

competition but is for the protection of the public.”); Gardner,

48 N.W.2d at 794 (“purpose is to protect the public from the intolerable evils

which are brought upon people by those who assume to practice law without

having the proper qualifications”); Cape May County Bar Ass'n v. Ludlam,

211 A.2d 780, 782 (N.J. 1965) (purpose

behind prohibiting the unauthorized

practice of law is to protect the

public against incompetent legal work); People v. Alfani, 125 N.E. 671,

673 (N.Y. 1919) (purpose is “to protect the public from ignorance,

inexperience, and unscrupulousness”); State v. Buyers Serv. Co., 357

S.E.2d 15, 19 (S.C. 1987) (purpose is to “protect the public from receiving improper

legal advice”).

[36] See Witkin, supra, note

19.

[37] Roger B. Myerson, Game Theory: Analysis of Conflict

1 (1991).

[38] Shaun P. Hargeaves Heap and

Yanis Varoufakis, Game Theory: A Critical Introduction 81-82, 168-170

(1995).

[39] Orley Ashenfelter, David E. Bloom, and Gordon B. Dahl, Lawyers

as Agents of the Devil in a Prisoner’s Dilemma Game, 10 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 399 (2013) (using empirical analysis to

show that these prisoner’s dilemma dynamics do, in fact, induce competitive

behavior in the legal field).

[40] Hargeaves Heap and Varoufakis, supra note 38, at 170-174.

[41] Roger E.

Schechter, Changing Law Schools to Make Less Nasty Lawyers, 10 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 367, 380 (1997)

(“Unlike the “litigation explosion”--where there is a debate over whether the

problem exists at all--there does not seem to be much written argument claiming

that the civility crisis is being exaggerated.”); see also Mary Ann Glendon, A Nation

Under Lawyers: How the Crisis in the Legal Profession is Transforming American

Society 5 (1994) (citing how conduct once not tolerated is now widely

practiced); Anthony T. Kronman, The Lost Lawyer: Failing Ideals of the Legal

Profession 1 (1993) (arguing that “the profession now stands in danger of

losing its soul”); Sol M. Linowitz, The Betrayed Profession: Lawyering at

the End of the Twentieth Century (1994) (blaming the profession's decline,

in part, on a desire to seek high salaries); Russell G. Pearce, The

Professionalism Paradigm Shift: Why Discarding Professional Ideology Will

Improve the Conduct and Reputation of the Bar, 70 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1229 (1995) (recommending a

business paradigm to replace the professionalism paradigm in legal ethics).

[42] Schechter,

supra note 41, at 380 (“While

small-town lawyers in remote and bucolic corners of the country may continue to

treat each other with some degree of professional courtesy, that there is a

problem in most of the more populous places where law is practiced seems

undeniable.”); Joseph

Guy Rollins, The Way We Were Fifty Years Ago, 33-OCT

Hous. Law. 29, 34 (1995) (“My

first eleven years of practice were in a small town, and I remember with

pleasure and nostalgia the civility and pleasant relationship between lawyers,

judges, and court personnel. Even in Houston courtrooms in the late 1950’s

there was almost the same small town friendliness. It is a shame that this has

been lost.”).

[43] Roy B. Flemming, If You Pay

the Piper, Do

You Call the Tune?

Public Defenders in America's Criminal Courts, 14 Law & Soc. Inquiry 393, 397-400 (1989).

[44] John

Lande, Possibilities for Collaborative Law: Ethics and Practice of Lawyer

Disqualification and Process Control in A New Model of Lawyering, 64 Ohio St. L.J. 1315, 1380-81 (2003) (“Moreover,

membership in local CL groups can help practitioners maintain reputations for

acting cooperatively.”).

[45] David A. Lax and James K.

Sebenius, The Manager as Negotiator 38-43, 154 (1986).

[46] Art

Hinshaw & Jess K. Alberts, Doing the Right Thing: An Empirical Study of

Attorney Negotiation Ethics, 16 Harv.

Negot. L. Rev. 95, 112 (2011) (“Pepe found that more than half of his

study's respondents believed that it was permissible to “facilitate” a

settlement agreement based on the false testimony if they found out about the

misstatement after the deposition. More

specifically, more than one-third of the respondents thought it was acceptable

to enter into a settlement agreement without disclosing the fact that the

deposition testimony was erroneous.”).

[47] Robert Axelrod, The Evolution

of Cooperation 12 (1984).

[49] Co-resolution was piloted in the

Franklin County Domestic Relations Mediation program beginning in June, 2012,

handling cases that screened as high-conflict.

In surveys collected from 44 participants, parties rated satisfaction

with their own coach at 4.8/5.0 and comfort with the opposing coach at 4.6/5.0. This indicates that the coaches were able to

help their respective parties while maintaining cooperation and civility across

the table. Co-resolution was also

piloted in labor relations disputes in School District 36, Surrey, British

Columbia (the largest school district in the province). One co-resolver in that pilot project

described co-resolution as advocacy without the typical spin or

gamesmanship—the negotiators were able to trust each other and cut to the

bottom line.

[50] See Cleveland Bar Assn.,

95 Ohio St.3d 91, Cincinnati Bar

Assn., 123 Ohio St.3d 107, and Brown, 121 Ohio St.3d 423 (As

discussed in the previous section, these cases involved an individual

negotiating on behalf of another either against an opposing attorney or party

to a pending legal action. Outside of a

contained process of dispute resolution, agreed to by both parties, judicial

decision-making through litigation is a possibility and negotiation assistance

must be conducted with accurate evaluation of what the court could do—this can

only be offered by legal counsel).

[51] Martin A.

Frey, Does Adr Offer Second Class Justice?, 36 Tulsa L.J. 727, 758 (2001) (“The parties in a mediated

agreement may elect to give up their legal rights in exchange for an outcome

that makes personal or business sense. The mediated agreement ends the dispute,

establishes certainty as to the rights and duties of the parties, and permits

the parties to move forward. At times, the parties have a continuing business

relationship that is enhanced by the mediated agreement.”).

[52] Joel

Kurtzberg & Jamie Henikoff, Freeing the Parties from the Law: Designing

an Interest and Rights Focused Model of Landlord/tenant Mediation, 1997 J. Disp. Resol. 53, 75 (1997) (“The

critics act as if mediators are faced with a choice between either

ignoring the law completely or imposing it on the parties. They fail to see that a third option exists,

perhaps because so many mediators fail to see this as well. This third

mediation approach attempts to “free the parties from the law” by embracing it

and enabling the parties to both fully understand it and to decide for

themselves whether they accept or reject its underlying principles.”).

[53] Jacqueline

Nolan-Haley, Self-Determination in International Mediation: Some Preliminary

Reflections, 7 Cardozo J. Conflict

Resol. 277 (2006).

[54] Witkin, supra, note 19, at 243-244 (one key dynamic within the

co-resolution structure is that each party’s ability to terminate the process

keeps the co-resolvers loyal to their assigned party—if one party felt “ganged

up on” they could terminate the process for all participants. Thus, co-resolvers are encouraged to explain

the right to walk away to the parties at the outset of the process.).

[55] For a model predicting settlement values given litigation costs and uncertainty, see John P. Gould, The Economics of Legal Conflicts, 2 J. Legal Stud. 279, 281-86 (1973); Sheila

F. Anthony, Antitrust and Intellectual

Property Law: From Adversaries to Partners, 28 AIPLA Q.J. 1, 36-37 (2000) (“In

such settlements, parties may give up rights that they would otherwise

vindicate if litigation costs and risks were not prohibitive.”); Jonathan T.

Molot, How Changes in the Legal Profession Reflect Changes in Civil

Procedure, 84 Va. L. Rev. 955,

959-60 (1998) (observing that “liberal pleading and discovery under the Federal

Rules have altered litigation dynamics by making lawsuits more expensive and

inducing settlements based on this expense.”).

[56] Speed Shore Corp. v. Denda,

605 F.2d 469, 473 (9th Cir.1979) (“It is well recognized that settlement

agreements are judicially favored as a matter of sound public policy. Settlement agreements conserve judicial time

and limit expensive

litigation.”); United

States v. McInnes, 556 F.2d 436, 441 (9th Cir.1977) (“[T]he law favors and

encourages compromise settlements.... [T]here is an overriding public interest

in settling and quieting litigation.”).

[57] See Section I., supra, footnotes

9-15.