An Intro to Innovation...

The first thing to note about innovation is where it comes from. While we turn to experts for mainstream knowledge and wisdom, innovation generally comes from normal, unsuccessful people. Yes, "innovation" plays a part in most mission statements and has a highly positive ring to it. But the reality is that innovation is most often a lower level person who is struggling with what he or she is given and who is telling higher-ups that they have it wrong. This is not the pleasant picture with which any of us envision innovation.

If you do not believe me and are fearful of following those that do not have experience or expertise, then consider the prevailing business literature. While members of all fields--academics, public servants, and private interests--benefit from producing new ideas, only businesses live or die by their ability to stay ahead of the curve. Experts on business should therefore provide the most well-wrought wisdom on locating innovation, and they will point you to mid-level troublemakers in your organization as sources of new ideas (see Wayne Burkan, Wide Angle Vision).

This observation indicates two important characteristics of innovators. First, innovators come from lower levels. Second, innovators struggle in the mainstream world. I believe that these traits both point to something about the vision and the motivation that is required to create new ideas. As to vision, innovators see the world (or certain aspects of it) differently from everyone else, leading to conflict with mainstream thinkers and causing them to struggle in the lower levels of their field or organization. As to motivation, innovators need to be able to challenge the very ground they stand on with unrelenting determination, a task that is better suited for outsiders and nonconformists than for well-paid, comfortable experts. The common characteristics of innovators therefore demonstrate who the potential innovators are and what they must possess and undergo to invent something.

Tips for Inventive Thinking...

First, what not to do. When most people set out to write a paper or in some way make an intellectual dent in their field, they chose a topic and then try to say something about it that hasn't already been said. However, starting with a specific focus severely limits your creative potential in ways that will take me at least a paragraph to explain. Also, when people set out to invent something, they zero-in on a problem/unfulfilled need or take something that exists and attempt to find a new use for it. These approaches also limit creativity and lead to inventions such as hamburger-earmuffs (it's a Simpsons reference people).

These methods are problematic because they tie the author down to a topic. If you start out by picking a subject matter, you may have limited yourself to a problem with no solution or one in which you personally can't see the solution. Starting out with a topic therefore gives you "tunnel vision" and limits your possibilities. If you decide to argue an issue or contribute to an existing train of thought, then the best you will do is add a building block to the existing landscape (and the blocks get smaller and less significant as they go up). Focusing on an issue or a source will thereby apply a "gravity" that hinders your potential. On top of these constraints, working under this common mode of analysis will bring you to address the same issues and problems as everyone else. Under these conditions, creating something new is all about searching for a subject matter that others have not explored (likely to be so narrow that it has little real importance) or writing about it better than everyone else (a gamble to be left to the well-paid experts).

Okay. So if you can't start out by picking an issue, problem, or solution to write about, then how can you do anything productive? The following is the system I've used to come up with quite a number of unique structures for dispute resolution and human interaction.

1. Create a structure by aimlessly combining or altering ideas/elements.

2. Evaluate the structure by surmising its potential and comparing it to the status quo.

3. Work backwards by focusing on the inconsistency between the structure and the status quo, searching for a revolutionary shift.

4. REPEAT until a quality structure is discovered.

Like brainstorming, this method enhances creative potential by allowing a degree of boundless thinking. Plus, its evaluation method aims to identify big ideas. Now for a more detailed explanation:

Create a Structure. The goal of this crucial step is to create with reckless abandon--do not attempt to create a certain effect or address a certain problem, just come up with ideas (and lots of them). However, not the product of random neutral firings, good structures will draw on the innovator's general knowledge of component parts he or she is working with. Creating a structure is therefore a process of combining or altering different ideas, even if the results initially seem incompatible or counter intuitive. My personal examples include combining lobbying reform and mediation, melding co-mediators and advocates, and bringing arbitrators to act as mediators. In each case, I followed my instincts in combining/altering concepts and then thought out how the concepts could work together and what potential benefits the new structure could accomplish. (This may seem like firing blindly, but as discussed below, the key is to propose many structures and abandon the vast majority that don't work).

Evaluate the Structure. In order to identify the structures that are meaningful and workable, simply ask what the new structure could accomplish. The key is to focus on the potential effects and avoid premature negative judgment. Premature negativity towards the idea may be correctly-channeled wisdom over the components of the new structure, but such thoughts may be inapplicable to the the new combination or alteration.

When an idea with potential is located, the next step of the evaluation process is to compare it to the status quo. Therefore, locate the goals and potential effects of the new structure and then identify the existing structures that share the same purpose. The significance and uniqueness of a new idea is often measurable by the degree to which it adds to, improves on, or contradicts current practices. A truly revolutionary idea will stand apart in distinct ways from existing ideas that attempt a similar function.

Work Backwards. Focusing on the inconsistency between the new structure and the previous system, see if the improvements of the new structure point to some incompleteness or vestige held over from prior conditions. The comparison between the new and the old will therefore reveal the unfulfilled need. Once the innovator has worked backwards to identify the problem that the new idea addresses, it then becomes possible to resume normal analysis--presenting the unresolved problem first and then introducing the new structure as the logical solution.

REPEAT. The key to this thought process is repetition. It would miraculous to find a brilliant structure on the first try, and it would clash with the scientific method to create an idea and then argue that it has value. The process of creating and then working backwards will therefore involve the conception of many unworkable ideas that should be filtered out and abandoned. To increase the chances of finding upon a gem, the aspiring innovator should apply this thought process repeatedly (in law school, I was doing this constantly). Repeating the first two steps (creating a structure and proposing its potential) will bring many yet-unthought-of ideas across the innovator's mind and attempt to filter through the nonsensical ones for something of value.

Unlike prevalent modes of inspiration that attempt to build a line of reasoning (stacking blocks, constrained by gravity), my method involves inventing and then working backwards analytically (flying around and then working through the path to the ground once something of value is discovered).

Creating Dispute Resolution Systems...

My personal experience with the above method was in designing cooperative systems of dispute resolution and human interaction. As a developing field, ADR provides a fertile environment for new ideas. In creating substance-specific ideas, I would chose an area of consistently problematic human relations and then find some way of applying mediation or some negotiation-based, cooperative, positive-sum model. In creating substance-neutral ideas, I would combine or alter certain elements of dispute resolution processes or play around with roles and relationships among and of their component parts.

Now keep in mind that I never became too attached to an idea until it had presented sufficient potential. What I would do is take a class that involved writing a paper. Then I would spend the first couple of weeks (as I was learning about the subject) tossing around various ideas for structures to write about. I would go through many ideas covering a wide range of topics, find a few ideas that had possible potential, and then settle on the one that presented the most drastic shift over prevailing thought.

Note that I was focusing on the basics of a subject (reading the material for the first week or two) when I was tossing these ideas around. I believe that using basic ideas on a subject as the component parts of the proposed structure creates the most potential for revolutionary ideas. It seems to make sense that a new thought affecting the very base of a field, issue, or line of reasoning would have the largest effect. However, academics and theoreticians seem to value the more specific, highly-sophisticated topics. Whether this reveals a habit of searching for an unexplored area of study or an arrogant distaste for revisiting the basics, sticking to downstream, intricate subjects limits the big-picture impact of intellectual endeavors.

That is all for now. I hope these ideas will inspire innovators in dispute resolution, other social sciences, and beyond.

10.21.2008

9.28.2008

The Next Generation of Dispute Resolution Scholars

To explain my broader goals and where my ideas fit into the existing scholarship, I should first describe what I see as the calling for my generation of dispute resolution scholars.

The general duty of the first generation of dispute resolution thinkers was to create effective alternatives to formal, adversarial processes. In this endeavor, they succeeded wonderfully, mastering methods of facilitating negotiation and legitimizing mediation in the eyes of the law. As they continue this mission, however, it seems that they have hit a wall--people know about mediation and no one questions its legality, but people are not flocking to it as ADR advocates believed they would.

Simply assembling an army of mediation-trained professionals and releasing them into society may not be enough to change the system. Decisions and disputes remain at the hands of adversarial forums and unstructured negotiations. This is where the second generation of ADR scholars needs to step in. While the first generation created effective dispute resolution methods, the second generation must figure what to do with them (the DR skills, not the first generation).

Mediation is the most basic application of facilitation skills--one actor applies these techniques in a voluntary negotiation that parallels or supplements traditional processes. While mediation provides structure to the negotiation, the process itself enjoys no outside structural support (other than the enforcement of agreements as contracts) or internal protection (other than neutrality). And in the broader system, conflict is only brought to facilitated negotiation under the threat or force of litigation or another adversarial process, and mediation usually stands apart as a parallel, overlapping track to these forums. Because mediation is at the apex of dispute resolution, the movement is therefore a free-floating skill instead of a structure.

While this may be a reason that mediation remains underused, it also holds the potential for its revolutionary expansion--as a skill set, facilitated negotiation may be plugged into other systems to improve interactive processes. The failings of an "if you build it, they will come" strategy for mainstreaming mediation indicates the needs for more creative, integrated uses of this skill set. We therefore need to invent new processes and systems that integrate facilitated negotiation into standard decision-making and dispute resolution.

Allow me to be so presumptuous as to use myself as an example (because that phrase is presumptuous enough). To address corruption and inefficiency in Congress, I suggested a system in which interest groups would be subject to mediation based on a certain level of lobbying expenditures (see 23 Ohio St. J. on Disp. Resol. 373). The basic effect of this device is that Congress would be able to tell conflicting interest groups to negotiate under facilitation before bogging down their system with an overwhelming amount of indirect influence in lobbying (a real and increasing problem in legislatures nation-wide). While lobbying disclosure laws (the only regulation of lobbying ) have not reigned in these excesses, allowing Congress to pull specific conflicts to a process that will produce mutually-acceptable policies may decrease inefficient, improper lobbying. The implications for the ADR movement are that this idea involves mediation as an enforcement mechanism for a problem that is not connected to litigation.

For another example, consider the brilliant idea of my friend, Emily MacBeath. She proposed using mediation on couples that experience turbulence in getting engaged. Her system of Facilitated Engagement Planning will bring couples to discuss their individual dreams and conflicting interests so that they may negotiate their shared future as husband and wife. This idea may seem silly to older generations that were taught to value family, but today's younger generation was raised to value individualism (your life is not fulfilled unless you contribute something or backpack through Europe). When two such individuals attempt to meld their lives together (and inevitably sacrifice personal aspirations), they often experience tension no matter how much they love each other. To combat this conflict, Emily's mediator would encourage the parties to share their expectations and discuss difficult choices in a safe, facilitated environment. The implications to ADR scholarship are that there are no legal rights at play--most people would see this situation as being devoid of conflict (yeah right) and therefore impossible to mediate.

These ideas illustrate the capability of mediation to be applied and integrated into untested systems and situations. Facilitation skills, created and cultivated by the first generation of dispute resolution thinkers, have the potential to transform a wide range of human dynamics. Now that mediation is well-accepted and underused, the new scholars in our field will recognize its potential for new applications or will develop new processes as an attempt to break into steady, fulfilling ADR employment.

The general duty of the first generation of dispute resolution thinkers was to create effective alternatives to formal, adversarial processes. In this endeavor, they succeeded wonderfully, mastering methods of facilitating negotiation and legitimizing mediation in the eyes of the law. As they continue this mission, however, it seems that they have hit a wall--people know about mediation and no one questions its legality, but people are not flocking to it as ADR advocates believed they would.

Simply assembling an army of mediation-trained professionals and releasing them into society may not be enough to change the system. Decisions and disputes remain at the hands of adversarial forums and unstructured negotiations. This is where the second generation of ADR scholars needs to step in. While the first generation created effective dispute resolution methods, the second generation must figure what to do with them (the DR skills, not the first generation).

Mediation is the most basic application of facilitation skills--one actor applies these techniques in a voluntary negotiation that parallels or supplements traditional processes. While mediation provides structure to the negotiation, the process itself enjoys no outside structural support (other than the enforcement of agreements as contracts) or internal protection (other than neutrality). And in the broader system, conflict is only brought to facilitated negotiation under the threat or force of litigation or another adversarial process, and mediation usually stands apart as a parallel, overlapping track to these forums. Because mediation is at the apex of dispute resolution, the movement is therefore a free-floating skill instead of a structure.

While this may be a reason that mediation remains underused, it also holds the potential for its revolutionary expansion--as a skill set, facilitated negotiation may be plugged into other systems to improve interactive processes. The failings of an "if you build it, they will come" strategy for mainstreaming mediation indicates the needs for more creative, integrated uses of this skill set. We therefore need to invent new processes and systems that integrate facilitated negotiation into standard decision-making and dispute resolution.

Allow me to be so presumptuous as to use myself as an example (because that phrase is presumptuous enough). To address corruption and inefficiency in Congress, I suggested a system in which interest groups would be subject to mediation based on a certain level of lobbying expenditures (see 23 Ohio St. J. on Disp. Resol. 373). The basic effect of this device is that Congress would be able to tell conflicting interest groups to negotiate under facilitation before bogging down their system with an overwhelming amount of indirect influence in lobbying (a real and increasing problem in legislatures nation-wide). While lobbying disclosure laws (the only regulation of lobbying ) have not reigned in these excesses, allowing Congress to pull specific conflicts to a process that will produce mutually-acceptable policies may decrease inefficient, improper lobbying. The implications for the ADR movement are that this idea involves mediation as an enforcement mechanism for a problem that is not connected to litigation.

For another example, consider the brilliant idea of my friend, Emily MacBeath. She proposed using mediation on couples that experience turbulence in getting engaged. Her system of Facilitated Engagement Planning will bring couples to discuss their individual dreams and conflicting interests so that they may negotiate their shared future as husband and wife. This idea may seem silly to older generations that were taught to value family, but today's younger generation was raised to value individualism (your life is not fulfilled unless you contribute something or backpack through Europe). When two such individuals attempt to meld their lives together (and inevitably sacrifice personal aspirations), they often experience tension no matter how much they love each other. To combat this conflict, Emily's mediator would encourage the parties to share their expectations and discuss difficult choices in a safe, facilitated environment. The implications to ADR scholarship are that there are no legal rights at play--most people would see this situation as being devoid of conflict (yeah right) and therefore impossible to mediate.

These ideas illustrate the capability of mediation to be applied and integrated into untested systems and situations. Facilitation skills, created and cultivated by the first generation of dispute resolution thinkers, have the potential to transform a wide range of human dynamics. Now that mediation is well-accepted and underused, the new scholars in our field will recognize its potential for new applications or will develop new processes as an attempt to break into steady, fulfilling ADR employment.

9.24.2008

Special Thanks to...

I must start out by thanking the few crucial people that had a significant impact on the development of co-resolution.

The story of co-resolution through its supporting cast members starts with Carly Lane. She unintentionally inspired the idea by complaining about certain aspects of mediation (these events are described in the "Ah-ha moment" blog entry). Her pessimism identified the problem, and my optimism in the innovative potential of ADR took over from there. She then provided indirect emotional support by laughing at my jokes for the next two dateless years as I poured over this dispute resolution process. While she was pursuing her own ADR specialty and often paralleling my efforts, as to co-resolution she took a back seat--not driving, but along for the ride. That is, until the creation of this website--she designed and constructed everything you see here, and I would have been tangled up in the world wide web without her.

My gratitude next extends to Sarah Cole. I came up with the basic idea for co-resolution while in her mediation practicum. The process was embryonic at this point, so her major contribution at the time was not squishing it and sending me to a hospital for the unethically-insane (as others would threaten to do). And because she was always available and helpful, her research suggestions early on probably had disproportionally strong influence on the direction I took. Later, she became the primary supporter of my efforts, inviting me to speak about co-resolution to students and faculty members and helping me organize a simulation of the process.

The next person to impact the co-resolution idea was Nancy Rogers. While Prof. Cole was nurturing to the student that was going to fall on either side of the thin line between innovation and insanity, Nancy Rogers constantly challenged that student. Using her unmatched knowledge of dispute resolution, she forced me to confront the ethical issues I had created and pointed me to extremely useful, yet completely obscure articles. Furthermore, it was her flat-out rejection of the process's original name that led me to dub the process "co-resolution." In the end, my drive to impress her caused me, without a second thought, to turn a 20-page assignment into a 70-page omnibus paper that addressed aspects of co-resolution that I have yet to express anywhere else. I am therefore grateful for her sincere efforts to force me to succeed (also, she deserves thanks for merely reading through 70 pages of my nearly-unedited hypothesizing).

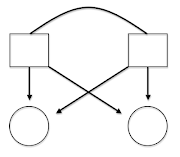

After the big three brought me to conceive, pursue, and develop the co-resolution process, I received crucial support from other members of the ADR community. Christopher Fairman, another professor and a master of the visual aid, met with me once and said something (I do not know what) that inspired me to create the chart that adorns this website and all other descriptions of co-resolution. Next, I am greatly indebted to Susan Raines for allowing me the huge opportunity to submit an article on co-resolution to Conflict Resolution Quarterly. I had been told by others that the journals would not waste their time on student submissions, and the response I received from her readers was a real turning point in my quest for legitimacy (they probably didn't know that I was a student). Credit is also due to Bernie Mayer and John Lande--both big names in ADR who took the time to aid and support me based on near-chance personal contacts. I accidentally ran into Dr. Mayer at a conference in Columbus and I volunteered to drive Prof. Lande to the airport after a symposium, but both were receptive to me as a random person who jumped out and assaulted them with an entirely made-up ADR concept.

Overall, considering the abrasive uniqueness of my idea and the tendency of people to resist change, nearly everyone in the ADR community was willing to listen and politely supportive, if not actually convinced, of my position. My experience, confirmed by my research on the subject, is that everyone claims to value innovation, but is repulsed when actually confronted with it. However, the ADR community (whether dangerously stable or dangerously insecure, depending on your perspective) proved to be a hospitable environment for new ideas.

The story of co-resolution through its supporting cast members starts with Carly Lane. She unintentionally inspired the idea by complaining about certain aspects of mediation (these events are described in the "Ah-ha moment" blog entry). Her pessimism identified the problem, and my optimism in the innovative potential of ADR took over from there. She then provided indirect emotional support by laughing at my jokes for the next two dateless years as I poured over this dispute resolution process. While she was pursuing her own ADR specialty and often paralleling my efforts, as to co-resolution she took a back seat--not driving, but along for the ride. That is, until the creation of this website--she designed and constructed everything you see here, and I would have been tangled up in the world wide web without her.

My gratitude next extends to Sarah Cole. I came up with the basic idea for co-resolution while in her mediation practicum. The process was embryonic at this point, so her major contribution at the time was not squishing it and sending me to a hospital for the unethically-insane (as others would threaten to do). And because she was always available and helpful, her research suggestions early on probably had disproportionally strong influence on the direction I took. Later, she became the primary supporter of my efforts, inviting me to speak about co-resolution to students and faculty members and helping me organize a simulation of the process.

The next person to impact the co-resolution idea was Nancy Rogers. While Prof. Cole was nurturing to the student that was going to fall on either side of the thin line between innovation and insanity, Nancy Rogers constantly challenged that student. Using her unmatched knowledge of dispute resolution, she forced me to confront the ethical issues I had created and pointed me to extremely useful, yet completely obscure articles. Furthermore, it was her flat-out rejection of the process's original name that led me to dub the process "co-resolution." In the end, my drive to impress her caused me, without a second thought, to turn a 20-page assignment into a 70-page omnibus paper that addressed aspects of co-resolution that I have yet to express anywhere else. I am therefore grateful for her sincere efforts to force me to succeed (also, she deserves thanks for merely reading through 70 pages of my nearly-unedited hypothesizing).

After the big three brought me to conceive, pursue, and develop the co-resolution process, I received crucial support from other members of the ADR community. Christopher Fairman, another professor and a master of the visual aid, met with me once and said something (I do not know what) that inspired me to create the chart that adorns this website and all other descriptions of co-resolution. Next, I am greatly indebted to Susan Raines for allowing me the huge opportunity to submit an article on co-resolution to Conflict Resolution Quarterly. I had been told by others that the journals would not waste their time on student submissions, and the response I received from her readers was a real turning point in my quest for legitimacy (they probably didn't know that I was a student). Credit is also due to Bernie Mayer and John Lande--both big names in ADR who took the time to aid and support me based on near-chance personal contacts. I accidentally ran into Dr. Mayer at a conference in Columbus and I volunteered to drive Prof. Lande to the airport after a symposium, but both were receptive to me as a random person who jumped out and assaulted them with an entirely made-up ADR concept.

Overall, considering the abrasive uniqueness of my idea and the tendency of people to resist change, nearly everyone in the ADR community was willing to listen and politely supportive, if not actually convinced, of my position. My experience, confirmed by my research on the subject, is that everyone claims to value innovation, but is repulsed when actually confronted with it. However, the ADR community (whether dangerously stable or dangerously insecure, depending on your perspective) proved to be a hospitable environment for new ideas.

The "Ah-ha" moment

I remember the scene vividly. I was walking out of a class on mediation with a friend and fellow dispute resolution scholar. As either a person with an internal equalizer or just an avid arguer, she tended to respond to pessimism with optimism and to optimism with pessimism. Therefore, after sitting through almost two hours of everyone high-fiving the mediation process, she felt the need to even things out (or just pick a fight with me, a fan of all things ADR). So she began to recount a mediation that she conducted in which one party became emotional and, when the other party offered the object of the dispute, turned off the emotion and snatched up the settlement. The moral of this story was, "What could the mediator do?" The parties had reached a settlement, and the mediator would lose their neutrality by calling out unfair negotiation tactics.

This scene became burned into my mind because it ignited something and sent my brain into overdrive. We just turned the corner when the moral of her story sank in, and it hit me. I stopped walking and, while fully taking in the art deco pattern on the adjacent wall, I thought, "Why not provide each party with a mediator to help them negotiate?" This question makes next to no sense to any expert on mediation and dispute resolution. But because I didn't know better, I was wrapping myself around all of the possibilities and benefits that this dynamic could spawn. This was my "Ah-ha" moment, a singular shift in my thinking from which everything else was to follow.

"What is it?" my friend asked. I was still frozen, staring at a wall. Embarrassed, I shook it off. "Uh. I just had an idea. It's nothing."

This scene became burned into my mind because it ignited something and sent my brain into overdrive. We just turned the corner when the moral of her story sank in, and it hit me. I stopped walking and, while fully taking in the art deco pattern on the adjacent wall, I thought, "Why not provide each party with a mediator to help them negotiate?" This question makes next to no sense to any expert on mediation and dispute resolution. But because I didn't know better, I was wrapping myself around all of the possibilities and benefits that this dynamic could spawn. This was my "Ah-ha" moment, a singular shift in my thinking from which everything else was to follow.

"What is it?" my friend asked. I was still frozen, staring at a wall. Embarrassed, I shook it off. "Uh. I just had an idea. It's nothing."

8.21.2008

Starting The Co-resolver

Welcome to The Co-Resolver. This blog will tell the story of the creation and spread of a new dispute resolution process. I held no position of authority or influence when I was developing and communicating these ideas, so this should be a pretty interesting story. It will be about innovation, the power of newcomers, and breaking into the field of Alternative Dispute Resolution.

Enjoy.

Enjoy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)