While I can present many arguments and hypotheses as to why the co-resolution structure will have a positive effect on negotiation, there is a simple reason for why this concept will work. The basic reason is that independence between advocates better serves adjudication, while dependence between advocates (as designed in co-resolution) better fits negotiation. This entry will therefore compare the nature of adjudication vs. negotiation and the function of attorneys vs. negotiators in order to arrive at the simple conclusion that negotiation operates better when the advocates have a stake in their continued interaction.

Adjudication is a full comparison by a third party of the evidence and arguments presented by each side in order to determine an objective Truth or just outcome. In order to fulfill this purpose, both parties are allowed the assistance of advocates, and the advocates are prevented from engaging in actions that undermine the adversarial, investigatory nature of adjudication. As a result, advocates must thoroughly oppose each other, conduct and keep their research apart, and maintain the freedom to package their cases in a light most favorable to their party.

In order to motivate full investigation and debate, and also allow for separate research and strategies, legal advocates must maintain complete independence from their opposition. One of the most protected rules of legal ethics, strict independence is so far ingrained in advocacy that no one argues its value in either direction. However, while this trait clearly enhances the overall functioning of adjudication, over 90% of legal cases settle in negotiation between the attorneys. And because they are geared towards debate, attorneys have difficulty in negotiation—they play games with strategy, use mere intuition in “feeling out” the other side, can only trust that the other side is working against them, and keep the negotiation on a simplistic, linear level.

These problems occur because negotiation and adjudication are very different processes. While adjudication is a backwards-focused debate-and-decision procedure, negotiation is a voluntary coming together of both sides into a mutual outcome, and it is therefore more cooperative in nature. When each process is at its best, adjudication indicates the deserving party, and negotiation allows both sides to get their most desired outcome in light of their conflicting needs. Negotiation under independent advocates is less an exploration of optimal solutions and more of an unregulated back-and-forth over what the parties deserve.

Just as it is well-known and intuitive that independence between advocates best serves the adjudication forum, it is similarly accepted that a relationship between negotiators enhances the interaction. Opposing advocates that foresee or have an interest in continued interaction with each other tend to have more fluid, comfortable, and productive negotiations. This is because having a relationship aligns the negotiators’ strategies and allows them to focus on using their knowledge and understanding of their separate sides to explore an optimal, mutually satisfactory outcome.

Therefore, because it is clear and obvious that independent advocates were specifically designed for adjudication, that negotiation and adjudication are different processes, and that relationships across the table increase the quality of negotiations, it should not be presumed that negotiators should offer their services independently. Despite the well-known effects of independence and dependence on the negotiation forum, when parties seek assistance in negotiation they continue to bring in independent negotiators.

This is the simple reason that co-resolution will work—it offers all of the benefits of independent counsel (loyalty, personal assistance) with the advantages of an across-the-table relationship (cooperation, trust). The co-resolution structure basically takes the elements of legal negotiation that were designed for the courtroom and brings them to better fit a negotiated interaction.

The Tractor Metaphor

While the following argument deserves to be a separate post, it works best as a supplement to the discussion of independent vs. dependent advocacy.

Adversarial litigation is accurately represented as a linear battle between the opposing parties. On any given issue, there are two possible adjudicated results, a negotiated compromise will fall at some midpoint along the variables in question (money, time), and each advocate pulls for an outcome that favors their side. Under the simple limitations of this forum, so long as these advocates pull in opposite directions skillfully and diligently, the process will be thorough and the end result will be just.

Advocates in adversarial adjudication are therefore two tractors, connected by a chain, playing tug-of-war. In order to ensure that each pulls to their full ethical extent, each tractor is provided and run by a different company. This arrangement motivates each tractor to constantly pull hard in order to attract business and makes it functionally impossible for the tractors to collude or gain unfair advantage. The use of independent tractors therefore makes sense in a linear contest between the two sides.

Interest-based negotiation is an entirely different creature from adversarial litigation. Instead of comparing diametric arguments and accounts to discern which side was correct, in negotiation, both sides discuss their aspirations and capabilities in a voluntary effort to arrange their joint or concerted future actions. The process is not a controlled clash of differing perspectives, but rather an endeavor to construct a shared framework for both sides.

Advocates that personally assist parties in negotiation are therefore two tractors that work together in one construction project. Despite the level of cooperation needed in this undertaking, both parties typically seek and provide tractors run by different companies. As a result, the tractors may not be compatible or able to function in a coordinated manner.

This accurately illustrates the use of independent advocates in negotiating a deal or mutual resolution to a conflict. Using advocates that have no relationship will make cooperation difficult and dangerous, place a number of obstacles in the way of smooth dealings, and limits the range of possible solutions. Meanwhile, because the parties must agree to a negotiated outcome (unlike a litigated outcome), a relationship across the table does not obstruct either advocate’s subservience to the party they negotiate for. Thus, while independent advocates fit into the purpose and structure of adversarial litigation, advocates that can comfortably work together and trust each other will conduct more productive and mutually beneficial negotiations.

9.07.2009

9.06.2009

The Difference Between Co-resolution and Collaborative Law

The basic differences between co-resolution and collaborative law are as follows:

Containing Cooperation.

As is has been identified in collaborative law, a "container" is a mechanism that limits the interaction between disputing sides to negotiation and settlement. Such a container is absolutely necessary in bringing two partisan negotiators to focus on cooperation.

In 1985, the great Roger Fisher proposed the idea of settlement counsel--attorneys that focus entirely on negotiating a resolution with the other side. However, the idea did not take off because, like the negotiation strategy in Getting to Yes, there was nothing holding the other side to limit themselves to the same cooperative approach. And because an experienced negotiator can covertly pursue one-sided advantages and a hard-nosed litigator can stall negotiations until they bring the unprepared opponent into court, it is not wise for one side to focus entirely on settlement. While the great minds in law and ADR were trying to invent a method for bringing the parties to focus on settlement (but thinking only from the perspective of one side trying to strategically affect the other), little-known Stu Webb came up with the idea of focusing both sides on settlement by creating a container around the negotiation process.

Webb's container is formed by opposing lawyers signing a contract stating that neither will litigate (containing the interaction to settlement negotiation) and that if the case goes to court, both lawyers will withdraw (enforcing the container). The success and popularity of this approach show that, for both sides to focus on assisting disputants in negotiation and negotiation alone, there must be some kind of container that prohibits selfish, adversarial strategies.

While the container created in collaborative law involves two parties seeking independent attorneys and then the attorneys limiting their assistance via contract, co-resolution creates a container by offering both negotiators/coaches ("co-resolvers") as a single service or process. Just as in collaborative law, the assistance provided is limited to negotiation because if the parties terminate the negotiation, they also terminate the assistance of both negotiators. However, the difference is that co-resolution creates a more tightly-knit, deliberate container.

In co-resolution, not only does the process end when the parties give up on negotiation, but the co-resolvers share a dependent relationship that influences their behavior and enforces cooperation.

As continuing partners in a single dispute resolution service who assist conflicting parties, the co-resolvers will negotiate against each other repeatedly. Because adversarial and deceptive negotiation tactics would be reciprocated later by the other side or at least sour their working relationship, both co-resolvers will fully cooperate with each other and coach their assigned parties in cooperative negotiation. And because the parties profit from this assistance, they have incentive to act under the co-resolvers' cooperative strategy. The need to maintain good relations across the table also prevents either co-resolver from overpowering the other side or supporting unreasonable positions (assertions that would offend a long-term negotiating relationship). Because both co-resolvers obey this ethic, the process will be balanced, fair, and neutral.

While collaborative lawyers can preclude litigation and motivate settlement, signing away the ability to go to court does not create this level of reliable cooperation and balanced advocacy.

Thus, instead of choosing independent attorneys--a role that is adversarial by design--and then wrapping them around a collaborative forum, co-resolution cuts right to employing two collaborative negotiators/coaches in a single, stand-alone process and then designing them to be cooperative and balanced.

The Four-Way Negotiation.

Comparing the negotiation procedures of co-resolution and collaborative law is slightly difficult because the later was developed organically, organized locally, and conducted by independent attorneys. As a result, practices and conceptions in collaborative law vary among local practice groups, legal scholars, and individual lawyers. Most notably, while the organization and boundaries of the forum (two attorneys agreeing to negotiate) are uniform, the procedures for conducting the negotiation do not seem to be set. The best I can nail down is that both attorneys use a variety of roles--including coach, advocate, problem-solver, and facilitator--and operate under methods described in Getting to Yes. Broad roles and values may be common to the ADR-focused attorneys that do collaborative law, but because they operate independently, there does not seem to be a uniform procedure that both sides employ.

Co-resolution, on the other hand, was developed in a laboratory setting and is conducted by two negotiators that are very familiar with each other--it therefore comes with a defined, mutual method of operation. Under the defined co-resolution strategy, each co-resolver directs supportive roles (coach, advocate, negotiator) to their assigned party and acts as a mediator to the other side--focusing them on interests, bringing them to expand their options, and explore solutions (anything that generates movement towards resolution). The most important part of this concept is that each co-resolver fully imitate a mediator only to the other side, together creating the effects of a single mediator but eliminating the need for impartiality. This set strategy provides each co-resolver with a consistent direction (assisting Party A and conciliating Party B constantly serves the interest of Party A) and organizes their efforts so that neither will violate party-loyalty by supporting/conciliating the wrong side. Furthermore, the co-resolvers follow a set sequence that parallels the seven-stage mediation model.

Therefore, while collaborative lawyers seem to operate the four-way negotiation with broad negotiation strategies and an undefined sequence, co-resolution (like mediation) offers specific guidelines for conducting the process. This is not to say that co-resolvers cannot develop their own methods or that familiar collaborative lawyers cannot use the co-resolution strategy (supporting one side, conciliating the other). The difference is that co-resolution is a more deliberate, organized process.

As a final note, some of the writing on collaborative law mention that the attorneys can provide the benefits of legal advice to their clients within the process. This is admittedly absent in co-resolution, where even attorneys acting as co-resolvers should not mention how a court would apply the law to the situation. However, I question whether legal advice is appropriate in collaborative law as well. First, agreeing not to litigate should take the parties' focus from legal rights to personal interests. Second, what a court may say should have no bearing, unless the agreement is so illegal that both attorneys fear that it would be overturned by a reviewing court.

In summation, collaborative law and co-resolution attempt to do the same thing, but the former does so with independent counsel who control behavior with contracts/rules, and the later does so with a team of mediation-trained professionals who operate under a close relationship and defined procedures. These differences in approach should produce significant differences in outcome.

- Collaborative law facilitates resolution with independent attorneys (they are chosen separately and then agree to cooperate). Co-resolution facilitates resolution with dependent negotiators (they come as a package deal and share a cooperative relationship).

- Collaborative law is designed to produce a negotiated settlement. Co-resolution is designed to produce reliable, cooperative negotiation methods throughout the process.

- Collaborative law is a type of legal advocacy and therefore requires attorneys. Co-resolution is a separate, independent process that only requires mediation-trained professionals.

Containing Cooperation.

As is has been identified in collaborative law, a "container" is a mechanism that limits the interaction between disputing sides to negotiation and settlement. Such a container is absolutely necessary in bringing two partisan negotiators to focus on cooperation.

In 1985, the great Roger Fisher proposed the idea of settlement counsel--attorneys that focus entirely on negotiating a resolution with the other side. However, the idea did not take off because, like the negotiation strategy in Getting to Yes, there was nothing holding the other side to limit themselves to the same cooperative approach. And because an experienced negotiator can covertly pursue one-sided advantages and a hard-nosed litigator can stall negotiations until they bring the unprepared opponent into court, it is not wise for one side to focus entirely on settlement. While the great minds in law and ADR were trying to invent a method for bringing the parties to focus on settlement (but thinking only from the perspective of one side trying to strategically affect the other), little-known Stu Webb came up with the idea of focusing both sides on settlement by creating a container around the negotiation process.

Webb's container is formed by opposing lawyers signing a contract stating that neither will litigate (containing the interaction to settlement negotiation) and that if the case goes to court, both lawyers will withdraw (enforcing the container). The success and popularity of this approach show that, for both sides to focus on assisting disputants in negotiation and negotiation alone, there must be some kind of container that prohibits selfish, adversarial strategies.

While the container created in collaborative law involves two parties seeking independent attorneys and then the attorneys limiting their assistance via contract, co-resolution creates a container by offering both negotiators/coaches ("co-resolvers") as a single service or process. Just as in collaborative law, the assistance provided is limited to negotiation because if the parties terminate the negotiation, they also terminate the assistance of both negotiators. However, the difference is that co-resolution creates a more tightly-knit, deliberate container.

In co-resolution, not only does the process end when the parties give up on negotiation, but the co-resolvers share a dependent relationship that influences their behavior and enforces cooperation.

As continuing partners in a single dispute resolution service who assist conflicting parties, the co-resolvers will negotiate against each other repeatedly. Because adversarial and deceptive negotiation tactics would be reciprocated later by the other side or at least sour their working relationship, both co-resolvers will fully cooperate with each other and coach their assigned parties in cooperative negotiation. And because the parties profit from this assistance, they have incentive to act under the co-resolvers' cooperative strategy. The need to maintain good relations across the table also prevents either co-resolver from overpowering the other side or supporting unreasonable positions (assertions that would offend a long-term negotiating relationship). Because both co-resolvers obey this ethic, the process will be balanced, fair, and neutral.

While collaborative lawyers can preclude litigation and motivate settlement, signing away the ability to go to court does not create this level of reliable cooperation and balanced advocacy.

Thus, instead of choosing independent attorneys--a role that is adversarial by design--and then wrapping them around a collaborative forum, co-resolution cuts right to employing two collaborative negotiators/coaches in a single, stand-alone process and then designing them to be cooperative and balanced.

The Four-Way Negotiation.

Comparing the negotiation procedures of co-resolution and collaborative law is slightly difficult because the later was developed organically, organized locally, and conducted by independent attorneys. As a result, practices and conceptions in collaborative law vary among local practice groups, legal scholars, and individual lawyers. Most notably, while the organization and boundaries of the forum (two attorneys agreeing to negotiate) are uniform, the procedures for conducting the negotiation do not seem to be set. The best I can nail down is that both attorneys use a variety of roles--including coach, advocate, problem-solver, and facilitator--and operate under methods described in Getting to Yes. Broad roles and values may be common to the ADR-focused attorneys that do collaborative law, but because they operate independently, there does not seem to be a uniform procedure that both sides employ.

Co-resolution, on the other hand, was developed in a laboratory setting and is conducted by two negotiators that are very familiar with each other--it therefore comes with a defined, mutual method of operation. Under the defined co-resolution strategy, each co-resolver directs supportive roles (coach, advocate, negotiator) to their assigned party and acts as a mediator to the other side--focusing them on interests, bringing them to expand their options, and explore solutions (anything that generates movement towards resolution). The most important part of this concept is that each co-resolver fully imitate a mediator only to the other side, together creating the effects of a single mediator but eliminating the need for impartiality. This set strategy provides each co-resolver with a consistent direction (assisting Party A and conciliating Party B constantly serves the interest of Party A) and organizes their efforts so that neither will violate party-loyalty by supporting/conciliating the wrong side. Furthermore, the co-resolvers follow a set sequence that parallels the seven-stage mediation model.

Therefore, while collaborative lawyers seem to operate the four-way negotiation with broad negotiation strategies and an undefined sequence, co-resolution (like mediation) offers specific guidelines for conducting the process. This is not to say that co-resolvers cannot develop their own methods or that familiar collaborative lawyers cannot use the co-resolution strategy (supporting one side, conciliating the other). The difference is that co-resolution is a more deliberate, organized process.

As a final note, some of the writing on collaborative law mention that the attorneys can provide the benefits of legal advice to their clients within the process. This is admittedly absent in co-resolution, where even attorneys acting as co-resolvers should not mention how a court would apply the law to the situation. However, I question whether legal advice is appropriate in collaborative law as well. First, agreeing not to litigate should take the parties' focus from legal rights to personal interests. Second, what a court may say should have no bearing, unless the agreement is so illegal that both attorneys fear that it would be overturned by a reviewing court.

In summation, collaborative law and co-resolution attempt to do the same thing, but the former does so with independent counsel who control behavior with contracts/rules, and the later does so with a team of mediation-trained professionals who operate under a close relationship and defined procedures. These differences in approach should produce significant differences in outcome.

9.05.2009

The Simplest Explanation of Co-resolution

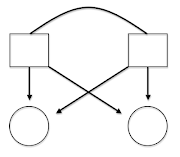

Co-resolution is a dispute resolution process in which two facilitators provide personal negotiation support to separate disputants. The facilitators act as continuing partners in a single dispute resolution service

As a team, these facilitators have a vested interest in their relationship with each other and will therefore only assist the parties in cooperative, principled negotiation strategies (as competitive, adversarial moves would harm their relationship).

Each facilitator then acts as a mediator only to the other side, thereby guiding the other party to focus on their interests, expand their options, and come to a resolution.

Because each facilitator loyally supports and coaches one side while conciliating the other side, each works in a consistent direction (helping one side) and together they act as a team in bringing the parties to resolution.

Co-resolution therefore performs all of the functions of mediation without the need for impartiality, and it inserts a cooperative level of personal support and coaching into the process to directly enhance the parties' experience in negotiation.

For more information, read the "About" tab in this website.

As a team, these facilitators have a vested interest in their relationship with each other and will therefore only assist the parties in cooperative, principled negotiation strategies (as competitive, adversarial moves would harm their relationship).

Each facilitator then acts as a mediator only to the other side, thereby guiding the other party to focus on their interests, expand their options, and come to a resolution.

Because each facilitator loyally supports and coaches one side while conciliating the other side, each works in a consistent direction (helping one side) and together they act as a team in bringing the parties to resolution.

Co-resolution therefore performs all of the functions of mediation without the need for impartiality, and it inserts a cooperative level of personal support and coaching into the process to directly enhance the parties' experience in negotiation.

For more information, read the "About" tab in this website.

9.04.2009

Co-resolution Free Info Sessions & November Training

In order to promote interest for a future training, I am offering free, one-hour info sessions on co-resolution at the downtown Columbus public library. The dates/locations are as follows:

Tuesday, 8/25: Conference Room #2

Tuesday, 9/1: Conference Room #2

Tuesday, 9/8: Conference Room #2

Wednesday, 9/16: Conference Room #2

Tuesday, 9/22: 3rd Floor Board Room

Tuesday, 9/29: 3rd Floor Board Room

Wednesday, 10/14: Conference Room #2

Wednesday, 10/28: 3rd Floor Board Room

The info sessions will be at 6:00-7:00 pm. Space is limited, so please email me at coresolution.adr@gmail.com if you plan on attending.

Also, I apologize for cancelling the July 17th training. I did not get enough people to contact me and sign up. So please contact me if you are interested in the next training.

I will hold another training on November 13th at the Convention Center. Hopefully, I'll be able to round up enough interest with the info sessions to make it worth the room charge.

Tuesday, 8/25: Conference Room #2

Tuesday, 9/1: Conference Room #2

Tuesday, 9/8: Conference Room #2

Wednesday, 9/16: Conference Room #2

Tuesday, 9/22: 3rd Floor Board Room

Tuesday, 9/29: 3rd Floor Board Room

Wednesday, 10/14: Conference Room #2

Wednesday, 10/28: 3rd Floor Board Room

The info sessions will be at 6:00-7:00 pm. Space is limited, so please email me at coresolution.adr@gmail.com if you plan on attending.

Also, I apologize for cancelling the July 17th training. I did not get enough people to contact me and sign up. So please contact me if you are interested in the next training.

I will hold another training on November 13th at the Convention Center. Hopefully, I'll be able to round up enough interest with the info sessions to make it worth the room charge.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)