Another promising idea of mine proposes a system of government that could be an optimal resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. This new system, called the Interspersed Nation-State System, allows governments to exist over certain people rather than over certain land. This means the state would tax and regulate its nationals, rather than tax and regulate everything that happens within certain borders (which is how the international system currently works).

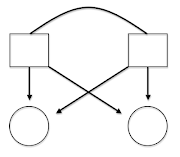

By shifting the locus of sovereignty (how the state delineates its power) from land to people, two nation-states would be able to exist in a shared region. Citizens of each state would have an independent government that tailors policies and public services to its nationals and would also have free movement over 100% of the disputed land. Let me state that again--two states would exist, and citizens of both states would have freedom of movement and full access to the shared homeland.

As applied to Israel and Palestine, citizens of each state would be able to live on the same street, Israelis would pay taxes to the Israeli government and send their children to Israeli schools, Palestinians would pay taxes to the Palestinian government and send their children to Palestinian schools. Police officers would enforce the laws of their separate states, would protect their own nationals, and in cases in which a citizen of one state commits a crime against a citizen of the other state, the victim's state would extradite the offender pursuant to the extradition treaty. Infrastructure would be handled by territorial local government, meaning that citizens of both states would participate in local decision-making, but also that this would handle non-political, shared resources such as roads and sewers.

The workings of this system are better and more-thoroughly explained in the most recent issue of The Middle East Journal (visit www.mei.edu). While the idea of two governments sharing land may sound more optimistic than realistic, my research indicates that the territory-based state is an outdated concept that is not designed to address modern conditions. In fact, the history of the territorial state (created in the 1600s) and the rise of nationalism (in the 1900s) indicate that the shift in sovereignty that I am proposing is the natural progression and is already occurring to some extent.

In conclusion, the Interspersed Nation-State System resolves problems that occur when distinct nations of people occupy one shared land and, therefore, are unable to satisfactorily divide up their spheres of influence with territorial state structures.

2.20.2011

2.09.2011

Further Ideas in Dispute Resolution: Consensus Arbitration

Allow me to depart from this blog's normal practice of blogging about co-resolution ONLY and then not blogging about anything for months at a time. More specifically, allow me to introduce you to consensus arbitration.

Consensus arbitration is a process in which the agreed-to arbitrator of the dispute does not write the award in isolation, but rather brings the parties together to discuss the shape of the award. The arbitrator would use his/her decision-making ability to guide the discussion (authoritatively, if necessary), but would otherwise act as a mediator. This would allow the parties to have a say in the specifics of the award and would allow the arbitrator to retain the ability to issue a final and binding decision.

This process is held out as the more natural and effective form of arbitration.

Under current arbitration practices, arbitrators imitate judges (by writing the award in isolation) even though their powers and functions are significantly different. Judges disseminate societal laws and norms upon everyone and, therefore, must be decisive and infallible. Also, judges preside over a completely thorough search for the Truth and, as a result, must weigh all admissible evidence in making a decision.

Arbitrators are different. Arbitrators are the predetermined resolvers of specific disputes between the parties and are described by the U.S. Supreme Court as an extension of the parties' negotiation or relationship--by entering into an arbitration agreement, the parties are presumed to have accepted, in advance, the arbitrator's decision, and the arbitrator is tasked with interpreting what the parties agreed to. Also, arbitrators preside over a more efficient/less thorough process and cannot be thought of as weighing as much evidence as a judge in rendering a decision. Finally, arbitrators are often chosen by both parties and, therefore, have incentive to appease both sides (whereas a judge is kept completely independent of the parties).

Thus, by imitating completely-decisive judges, arbitrators tend to render their own conceptions of acceptable compromises without consulting the parties. Instead, I argue, arbitrators should use their position as agreed-upon interpreter of the parties' agreement/negotiated relationship/best interests to act as a mediator who has the ability to render a decision.

To do this, the arbitrator would hear each side present their case (exactly as they normally do), but then, instead of withdrawing to write the award, would bring the parties together and mediate an agreement. And instead of acting as a detached, impartial mediator, the arbitrator would inform the parties of what he/she would be likely and not likely to put in an award, thereby guiding the parties to negotiate on the variables. This allows the arbitrator to retain influence and the final say, but also allows the parties to compromise and negotiate an acceptable resolution.

This process presents benefits of increased party satisfaction through control of/influence over the process. So why haven't arbitrators been doing this? Well, as it turns out, what I am describing as consensus arbitration used to be the normal method by which arbitrators render decisions. Prior to the acceptance of arbitration by the Courts in early-twentieth century American jurisprudence, arbitrators were described as a "mediator with a stick"--a person who consulted and advised the parties while retaining the ability to issue a decision. The change to a more legalistic, judge-like process occurred as the result of problems with enforcement of the arbitrator's private decision. However, today the Federal Arbitration Act and Steelworker's Trilogy (A New Hope, The Supreme Court Strikes Back, and Return of the Steelworkers) arbitration awards are fully enforceable and rarely overturned by state or federal courts.

Therefore, there is no longer anything preventing arbitrators from returning to their more natural, negotiated process. For further information on this process, read my article in Negotiation Journal (vol. 26 no. 3) or come hear my talk at the 2011 Fordham Law Conference on International Arbitration and Mediation. May the force (of arbitrators' decision-making power) be with you.

Consensus arbitration is a process in which the agreed-to arbitrator of the dispute does not write the award in isolation, but rather brings the parties together to discuss the shape of the award. The arbitrator would use his/her decision-making ability to guide the discussion (authoritatively, if necessary), but would otherwise act as a mediator. This would allow the parties to have a say in the specifics of the award and would allow the arbitrator to retain the ability to issue a final and binding decision.

This process is held out as the more natural and effective form of arbitration.

Under current arbitration practices, arbitrators imitate judges (by writing the award in isolation) even though their powers and functions are significantly different. Judges disseminate societal laws and norms upon everyone and, therefore, must be decisive and infallible. Also, judges preside over a completely thorough search for the Truth and, as a result, must weigh all admissible evidence in making a decision.

Arbitrators are different. Arbitrators are the predetermined resolvers of specific disputes between the parties and are described by the U.S. Supreme Court as an extension of the parties' negotiation or relationship--by entering into an arbitration agreement, the parties are presumed to have accepted, in advance, the arbitrator's decision, and the arbitrator is tasked with interpreting what the parties agreed to. Also, arbitrators preside over a more efficient/less thorough process and cannot be thought of as weighing as much evidence as a judge in rendering a decision. Finally, arbitrators are often chosen by both parties and, therefore, have incentive to appease both sides (whereas a judge is kept completely independent of the parties).

Thus, by imitating completely-decisive judges, arbitrators tend to render their own conceptions of acceptable compromises without consulting the parties. Instead, I argue, arbitrators should use their position as agreed-upon interpreter of the parties' agreement/negotiated relationship/best interests to act as a mediator who has the ability to render a decision.

To do this, the arbitrator would hear each side present their case (exactly as they normally do), but then, instead of withdrawing to write the award, would bring the parties together and mediate an agreement. And instead of acting as a detached, impartial mediator, the arbitrator would inform the parties of what he/she would be likely and not likely to put in an award, thereby guiding the parties to negotiate on the variables. This allows the arbitrator to retain influence and the final say, but also allows the parties to compromise and negotiate an acceptable resolution.

This process presents benefits of increased party satisfaction through control of/influence over the process. So why haven't arbitrators been doing this? Well, as it turns out, what I am describing as consensus arbitration used to be the normal method by which arbitrators render decisions. Prior to the acceptance of arbitration by the Courts in early-twentieth century American jurisprudence, arbitrators were described as a "mediator with a stick"--a person who consulted and advised the parties while retaining the ability to issue a decision. The change to a more legalistic, judge-like process occurred as the result of problems with enforcement of the arbitrator's private decision. However, today the Federal Arbitration Act and Steelworker's Trilogy (A New Hope, The Supreme Court Strikes Back, and Return of the Steelworkers) arbitration awards are fully enforceable and rarely overturned by state or federal courts.

Therefore, there is no longer anything preventing arbitrators from returning to their more natural, negotiated process. For further information on this process, read my article in Negotiation Journal (vol. 26 no. 3) or come hear my talk at the 2011 Fordham Law Conference on International Arbitration and Mediation. May the force (of arbitrators' decision-making power) be with you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)